Posted in: Aha! Blog > Wit & Wisdom Blog > Implementation Support > Distilling the Essence

Great Minds® teacher-writer Emily Gula continues her conversations with students and teachers around the country to learn about their success with Wit & Wisdom®.

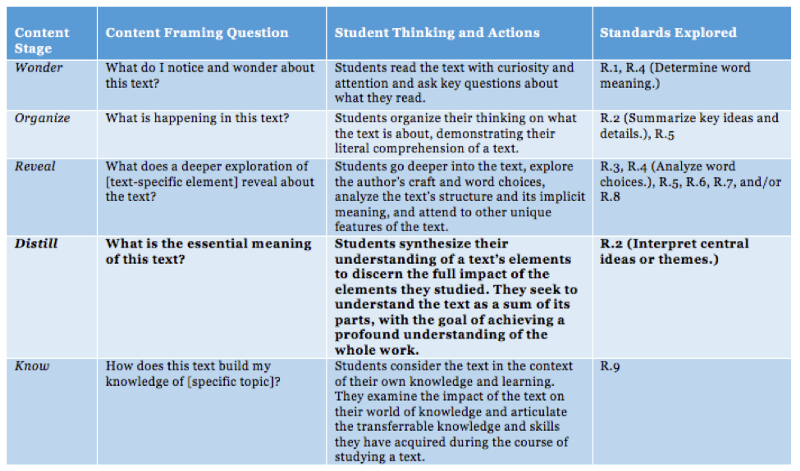

In our last post, we discussed how the Reveal stage guides students into diving into the gold of each text through targeted analysis. Each of these stages builds an important habit of mind to help students closely read complex text.

It’s sugaring season here in New Hampshire. Once the maple sap starts running, sugar makers collect the sap in storage containers and bring it to the sugarhouse where the water is boiled off. The sap boils for hours in metal evaporating pans heated by a wood fire or oil, leaving behind a concentrated syrup—and filling the sugarhouse with maple-infused steam. The process requires significant effort, but breakfast fans—including my children—will tell you it’s worth it.

As students in Wit & Wisdom classrooms approach the fourth Content Stage, Distill, they, too, are focused on a process to capture the essence—but that of a text rather than sap. They capture that essence through discussion and writing. Like syrup makers, students start with a mixture of elements which are then distilled, or refined, until what matters most is left behind. After examining text evidence, students synthesize their thoughts to answer the Content Framing Question: What is the essential meaning of this text?

I talked with prekindergarten and kindergarten inclusion teacher Dana Stiles and first-grade teacher Seshmi Taylor from E.L. Haynes Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., to learn more about what Distill lessons look like with their students.

IDENTIFYING THE ESSENTIAL MEANING

During the Organize stage students determine what a text is about, identifying story elements or the main topic. The process of organizing a text prepares students to think about its deeper meaning during the Distill stage, when they review significant details to home in on the central ideas and themes. While students use different terms from the standards depending on what kinds of texts they are studying (main or central idea when discussing informational texts, and central message or theme with literary texts), these terms refer to a similar outcome: the big ideas, or essential meaning, of a text.

In their study of the Wit & Wisdom module Powerful Forces—an exploration of the wind and emotions—Taylor’s first-graders read Brave Irene, a story about a girl on a mission to deliver a dress during a blizzard. When Taylor’s class discussed the central message, they determined how the details and lessons they learned from the story fit together. One student shared how the story was about “never giving up…” which another student expanded upon with “…even when things are difficult.” The central message of persisting despite challenges is rooted in the text, but goes beyond the topic of the text itself. By boiling down the essential meaning during this stage into a sentence or less, students consolidate their thinking into a portable phrase that can be carried forward to make connections with future learning.

SUPPORTING WITH EVIDENCE

During the Distill stage, students sort through the most significant textual evidence to see what essential meanings the evidence leads them to. When Stiles works with students in small groups, she says, “Show me where in the text,” and asks them to point to key supporting details which she records on an anchor chart. Grounding the essential meaning in evidence “is the key,” she says.

Distilling the essential meaning is challenging, especially for younger students who are still learning to read complex texts. At the beginning of the year, Taylor did more modeling to break down the Distill process. She provided students with two possible central messages, and then students determined which was best supported by text evidence. As Taylor read the book aloud, students annotated the pages with sticky notes to mark supporting evidence.

“I could see them thinking and eager to figure things out…It felt like research to them,” says Taylor. By diving back into the text and then taking a step back to synthesize, students saw the book in a new way. Now that Taylor’s students are more adept at the process, they can “generate the central message” themselves “either individually or with partners or small groups,” she says.

Similarly, Stiles structures her lessons to ensure students do more of the heavy lifting themselves over time. Many of her students receive additional pull-out support. For these students, Stiles scaffolds the steps during small-group instruction by extracting key scenes from the text and asking guiding questions to empower students to answer the “essential meaning question on their own.” During their study of the module America, Now and Then, kindergarten students examined the concepts of past and present by reading texts such as The Little House. To help her students identify the central message of The Little House, Stiles showed them pictures from the beginning of the story when the house is surrounded by the countryside. She then contrasted those images with images from later in the story, when the house is in the middle of a city. Stiles explains, “If students can understand that those are the major shifts in the story, they are able to fill in the blanks in-between.” When scaffolding the process, Stiles asks herself, “What is going to give me the most leverage for helping students to understand the essential meaning?” In the case of The Little House, it is how neighborhoods “change over time.”

Similarly, Stiles structures her lessons to ensure students do more of the heavy lifting themselves over time. Many of her students receive additional pull-out support. For these students, Stiles scaffolds the steps during small-group instruction by extracting key scenes from the text and asking guiding questions to empower students to answer the “essential meaning question on their own.” During their study of the module America, Now and Then, kindergarten students examined the concepts of past and present by reading texts such as The Little House. To help her students identify the central message of The Little House, Stiles showed them pictures from the beginning of the story when the house is surrounded by the countryside. She then contrasted those images with images from later in the story, when the house is in the middle of a city. Stiles explains, “If students can understand that those are the major shifts in the story, they are able to fill in the blanks in-between.” When scaffolding the process, Stiles asks herself, “What is going to give me the most leverage for helping students to understand the essential meaning?” In the case of The Little House, it is how neighborhoods “change over time.”

EXPERIENCING THE “AH-HA”

Distilling a text takes practice and patience, but students “take pride in being able to really understand the text and being able to talk confidently about it,” says Stiles. Her students like the “ah-ha moment” when they can say to themselves, “I got it.” When her students leave their small group to return to the general education classroom, they notice that “they are reading the same book” as the rest of their classmates. Stiles says, “We’re working through the same questions at the same time. That’s great for students.”

Distilling a text takes practice and patience, but students “take pride in being able to really understand the text and being able to talk confidently about it,” says Stiles. Her students like the “ah-ha moment” when they can say to themselves, “I got it.” When her students leave their small group to return to the general education classroom, they notice that “they are reading the same book” as the rest of their classmates. Stiles says, “We’re working through the same questions at the same time. That’s great for students.”

Identifying the essential meaning of a text leads to a profound understanding of the whole work. Taylor explains how her first-graders can now “take the whole story and put the parts together to come up with the central message.” She adds, “The number of students that are at or above grade level in reading since the beginning of the year has increased significantly…We can definitely see the fruits of our labor.”

Speaking of labor, it takes about forty gallons of sap to create one gallon of maple syrup. Producing maple syrup—or distilling a text—is a challenging process which takes time and patience. The outcome, however, is worth savoring.

Works Cited

Keller, Kristin Thoennes. From Maple Trees to Maple Syrup. Capstone Press, 2005.

For more information about maple syrup production, elementary readers may want to check out Sugaring, written by Jessie Haas and illustrated by Joseph A. Smith, as well as Maple Syrup Season, written by Ann Purmell and illustrated by Jill Weber.

Submit the Form to Print

Emily Gula

Emily Gula is a content lead at Great Minds, where she led a team of teacher-writers in creating the first-grade modules of Wit & Wisdom. Emily began her career teaching elementary school in New Orleans, then worked in New Orleans schools as a reading interventionist and literacy coach.

Topics: Implementation Support